Back to Iraq

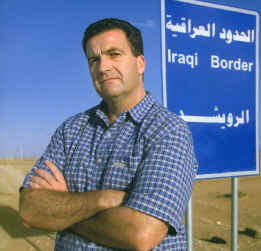

In November 2000 John Nichol returned to Iraq with The Daily Mirror and BBC Breakfast.

WITH trembling hands, John Nichol touches the graffiti scrawled across the four walls which once imprisoned him. When he was last here, the former RAF navigator was a prisoner of war, suffering from days of torture and interrogation at the hands of his Iraqi captors and uncertain if he would ever see his family again. Today he is a free man, revisiting his horrific past and trying to make sense of what happened to him. Nothing could have prepared him for the emotion he feels ten years back in the Iraqi prison cell where he thought he would be executed. "When I was in captivity, there were times I thought my life might have ended. I truly believed I was going to meet my maker." he says. "Words can't describe how I feel. Emotionally drained, uncomfortable. My heart is pounding. I just can't believe I'm here." John was a 27-year-old flight lieutenant when his Tornado was shot down over the Iraqi desert during his first airborne mission of the Gulf War. He and his pilot, John Peters, ejected safely from the blazing jet, only to be captured at the start of nearly two months of torture and interrogation. Forced by the Iraqis to appear on television and denounce their own actions, their battered faces were flashed across the world, lasting images of the horrors of war. Their submission came after a catalogue of mental and physical abuse which began when the airmen refused to reveal more than name, rank and number. While Allied jets continued to bomb the air base where they were being held, John, blindfolded and handcuffed, was kicked and punched by a group of guards. He was forced to stand with his feet twenty inches from the wall with his forehead against it, bearing his entire body weight. When he moved, he was whipped, his head smashed into the wall, his face kicked until blood poured down his flying suit. Cigarette ends were extinguished on his face, but he still didn't capitulate - not until they stuffed tissue paper down his neck and set fire to it. "For me, appearing on television signified my failure." says John. "I felt like a coward. I have never watched the footage. I couldn't bear it. "The worst thing wasn't the torture itself, it was the fear of the unknown. The fear of fear. "I dreaded doors clanking and footsteps because I'd be thinking: 'what are they going to do now'? "I can remember sitting in a chair, blindfolded and I knew there were people around me. I could feel the malevolence. But in a way, it was a relief when they started hitting me. Despite the pain, at least I knew what was happening."

WITH trembling hands, John Nichol touches the graffiti scrawled across the four walls which once imprisoned him. When he was last here, the former RAF navigator was a prisoner of war, suffering from days of torture and interrogation at the hands of his Iraqi captors and uncertain if he would ever see his family again. Today he is a free man, revisiting his horrific past and trying to make sense of what happened to him. Nothing could have prepared him for the emotion he feels ten years back in the Iraqi prison cell where he thought he would be executed. "When I was in captivity, there were times I thought my life might have ended. I truly believed I was going to meet my maker." he says. "Words can't describe how I feel. Emotionally drained, uncomfortable. My heart is pounding. I just can't believe I'm here." John was a 27-year-old flight lieutenant when his Tornado was shot down over the Iraqi desert during his first airborne mission of the Gulf War. He and his pilot, John Peters, ejected safely from the blazing jet, only to be captured at the start of nearly two months of torture and interrogation. Forced by the Iraqis to appear on television and denounce their own actions, their battered faces were flashed across the world, lasting images of the horrors of war. Their submission came after a catalogue of mental and physical abuse which began when the airmen refused to reveal more than name, rank and number. While Allied jets continued to bomb the air base where they were being held, John, blindfolded and handcuffed, was kicked and punched by a group of guards. He was forced to stand with his feet twenty inches from the wall with his forehead against it, bearing his entire body weight. When he moved, he was whipped, his head smashed into the wall, his face kicked until blood poured down his flying suit. Cigarette ends were extinguished on his face, but he still didn't capitulate - not until they stuffed tissue paper down his neck and set fire to it. "For me, appearing on television signified my failure." says John. "I felt like a coward. I have never watched the footage. I couldn't bear it. "The worst thing wasn't the torture itself, it was the fear of the unknown. The fear of fear. "I dreaded doors clanking and footsteps because I'd be thinking: 'what are they going to do now'? "I can remember sitting in a chair, blindfolded and I knew there were people around me. I could feel the malevolence. But in a way, it was a relief when they started hitting me. Despite the pain, at least I knew what was happening."

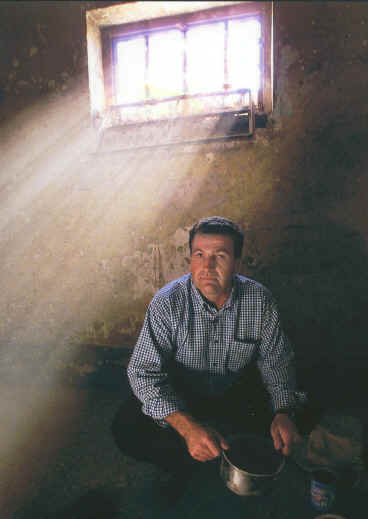

Days after submitting to the humiliating TV appearance, John was brought here, still blindfolded and handcuffed, to the Military Police Headquarters in the Iraqi capital, Baghdad. Crouching in the dust, John is absorbed by his past, examining in minute detail the empty nine-foot cell which is lit up by the midday sunlight pouring in through iron bars high above his head. The smell of decay is unbearable, but John doesn't seem to notice as he works his way around the discoloured, flaking walls, inch by inch. Amidst the Arabic graffiti left by other prisoners, pictures of women cut from newspapers have been glued to the cob-web covered plaster. He runs his hand over the rusting steel door which was once closed, locked and bolted against him. The stone floor is covered with pieces of rubble and rags, the beige walls are pitted with holes which as a prisoner, John feared were the marks left by bullets. During his time here, John's only companions were a piece of foam for his bed, two blankets and a jug of water. He was locked up for 24 hours a day, only allowed into the yard to exercise for ten minutes every couple of days. Once a day he was brought a meal consisting of bread, watery soup, and sometimes chicken, mutton or beans. There were no toilets in the cells. John and his fellow prisoners, who included pilot John Peters and other British and American prisoners of war, used a pit at the end of the corridor, which quickly overflowed. Left unguarded for much of the time, John was able to communicate with the other men by shouting to them - a luxury previously denied to him. "The first time I was brought here I was terrified for my life. I was the most scared human in the world." he says gazing at his surroundings. "I had been blindfolded and handcuffed and interrogated for three days and then in the middle of the night I was kicked awake and dragged out of my cell and brought here. "When they took the blindfold off I was standing in front of a group of Iraqi military policemen. Unlike the previous guards they didn't hurt me but I was scared. "Today, standing in front of me are a group of Iraqi military policemen, but this time, they are smiling and shaking hands and offering tea. It couldn't be more different. I can't believe how welcoming they are." John jumps visibly at the sound of the iron doors banging shut in the corridors behind him. "That was the sound I heard every day when the guards came to see us." he says. "It's so familiar. Even after all this time." he says. "I can't believe I'm back. "I'm pleased I've made myself do this, but having said that, I won't be sorry to leave. It just brings it all back." John has reached the end of a journey, a journey which began a decade ago when his Tornado was hit by a Surface-To-Air Missile over the Iraqi desert and he was taken prisoner.

Days after submitting to the humiliating TV appearance, John was brought here, still blindfolded and handcuffed, to the Military Police Headquarters in the Iraqi capital, Baghdad. Crouching in the dust, John is absorbed by his past, examining in minute detail the empty nine-foot cell which is lit up by the midday sunlight pouring in through iron bars high above his head. The smell of decay is unbearable, but John doesn't seem to notice as he works his way around the discoloured, flaking walls, inch by inch. Amidst the Arabic graffiti left by other prisoners, pictures of women cut from newspapers have been glued to the cob-web covered plaster. He runs his hand over the rusting steel door which was once closed, locked and bolted against him. The stone floor is covered with pieces of rubble and rags, the beige walls are pitted with holes which as a prisoner, John feared were the marks left by bullets. During his time here, John's only companions were a piece of foam for his bed, two blankets and a jug of water. He was locked up for 24 hours a day, only allowed into the yard to exercise for ten minutes every couple of days. Once a day he was brought a meal consisting of bread, watery soup, and sometimes chicken, mutton or beans. There were no toilets in the cells. John and his fellow prisoners, who included pilot John Peters and other British and American prisoners of war, used a pit at the end of the corridor, which quickly overflowed. Left unguarded for much of the time, John was able to communicate with the other men by shouting to them - a luxury previously denied to him. "The first time I was brought here I was terrified for my life. I was the most scared human in the world." he says gazing at his surroundings. "I had been blindfolded and handcuffed and interrogated for three days and then in the middle of the night I was kicked awake and dragged out of my cell and brought here. "When they took the blindfold off I was standing in front of a group of Iraqi military policemen. Unlike the previous guards they didn't hurt me but I was scared. "Today, standing in front of me are a group of Iraqi military policemen, but this time, they are smiling and shaking hands and offering tea. It couldn't be more different. I can't believe how welcoming they are." John jumps visibly at the sound of the iron doors banging shut in the corridors behind him. "That was the sound I heard every day when the guards came to see us." he says. "It's so familiar. Even after all this time." he says. "I can't believe I'm back. "I'm pleased I've made myself do this, but having said that, I won't be sorry to leave. It just brings it all back." John has reached the end of a journey, a journey which began a decade ago when his Tornado was hit by a Surface-To-Air Missile over the Iraqi desert and he was taken prisoner.

On January 17, 1991, it took just 60 minutes to fly from Muharraq air base in Bahrain to the target he and his pilot John Peters were ordered to bomb - Ar Rumaylah air base in southern Iraq. Ten years on, his pilgrimage back to Iraq has taken over a week - a seemingly endless journey across hundreds of miles of parched desert. Today, he is determined to put the horrors of the past behind him and make the Iraqis his friends. "It's not that I haven't come to terms with the past." He explains. "But I wanted to come back and meet the Iraqi people as real people, not just as the enemy. "Things are very different when there is a war on. I first came here to bomb the Iraqis. When you consider that, it's amazing how friendly they've been this time around." Blindfold for most of his time in captivity, 37-year-old John was initially uncertain of the various locations he was held prisoner - his captors never told him where he was being taken. He has vague memories, mental images of corridors and walkways, courtyards and prison walls, but, until now, no names. When we arrive at the Military Police headquarters, he stares at the soldiers guarding the giant white iron gates, taking in everything around him, but saying virtually nothing. Like most of our encounters with authority in Iraq, our visit begins with a meeting with bemused but friendly prison officials. We drink sweet Arabic tea while John explains who he is and why he is here. "You were a prisoner here?" says one incredulously. "I may have been." replies John. "I just don't know. I need your help to find out." We are eventually given permission to go into the prison and drive towards another set of gates, overshadowed by palm trees and one of several giant portraits of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein and more guards, dressed in olive green uniforms and red berets. We are introduced to prison commander, Brigadier Sa'ad Minim, who smiling hesitantly, shakes our hands and promises to do whatever he can to help us. Then, as we walk into the prison enclosure, John's face suddenly lights up. "I think this might be it." He says excitedly. "I really think this is the one." His memory has been triggered by a simple band of red, painted around the top and bottom of the white walls of the one-storey prison blocks. "There was a small barred window high up in my cell." he explains. "If I jumped up I could just make out this red band running around the tops of the buildings. I can remember that and the palm trees." Brigadier Minim and his men take us around several barbed-wire covered blocks, while John attempts to describe the courtyard he remembers glimpsing through the bars of his cell. We are shown two courtyards, John recognises neither of them and our spirits are beginning to fail. The giant rusting steel door to a third enclosure surrounded by barbed wire is locked. John stares through a tiny window in the door and turns round smiling. "Oh my God! This is definitely it." He says triumphantly. "This is it." Empty for seven years, the key to the disused block has long been lost, but realising how anxious we are to see inside, the Brigadier orders his men to force the door down with sledgehammers. Minutes later, surrounded by over 30 guards, we are standing inside the sun-drenched courtyard. While the armed guards look on in amazement, John is racing around the four walls, peering into the barred windows of the corridors, trying to find his own cell. John spent 11 days of his seven weeks as a prisoner of war inside this prison, a place he and his fellow captives christened 'The Baghdad Bungalows'. "Seeing the prison again took me back to some of my darkest days" he says. Despite his ordeal as a POW, his stay here, he says, was one of the more bearable times in captivity. "In many ways I didn't want to remember, but I'm glad that we came back to this prison in particular because I was treated as a prisoner of war here, with respect. "I don't think I could have faced revisiting the bad places. "I don't really like to talk about those times now. I have never watched those pictures of me from Iraqi television because for me they signify my biggest failure. I was forced to go on television and denounce what I had done." He explains to the Brigadier: "When I was in your prison, I was treated with dignity. "Your men were good to me. We had food to eat and no beatings."

The Brigadier smiles and replies in Arabic: "This is part of our nature to treat everybody in an excellent way." Despite the terror of his time in Iraq, John confesses to feeling a certain fondness for his time in this prison. On one occasion, he was summoned by the guards to play football with them. "They came into my cell and asked me if I could play." says John smiling. "When I said yes, we came out here into the courtyard and they put me in goal. "They kept shouting "Gascoigne", and "Kevin Keegan" at me, and I'd nod and say "yes, they are good footballers. It was bizarre." Minutes later, after John's story has been explained to the Brigadier, he has summoned his guards - and a football - and an impromptu game begins. It is a bizarre, but emotional scene. John, casually dressed in jeans and a shirt, kicks the ball to the Iraqi guards, who despite the blistering heat and their heavy uniforms, throw themselves vigorously into the game. Within moments, the courtyard is echoing with the sounds of shouts and laughter as John and the men tackle each other playfully. Dozens of other officers pack into the courtyard, cheering them on and clapping and cheering. When the game ends, the Iraqi players hug and kiss him on both cheeks, asking to have their photograph taken with the curious British airman who was once their prisoner. "You have an excellent football team" he says to the Brigadier. "I think it's Iraq 2, England 0." The Brigadier signals that it is time to leave and insists we join him for tea inside a gazebo built from palm trees and specially reserved for guests. John takes one last lingering look at the cell before turning and following the Brigadier, attempting to make conversation with the help of a translator. "Sometimes when you don't play for a long time and then you come back, you are very unfit." The Brigadier tells him, smiling and fingering a set of turquoise worry beads. John laughs and nods in agreement. The Brigadier adds: "It's all the drinking you have been doing." "You have been spying on us" jokes John through the translator. When we are invited to stay for lunch, he adds: "If we say no, will you allow us to leave?" "Of course", smiles the Brigadier, "You are free to go." The last time, John heard these words spoken was on March 5, 1991. After being moved to two other prisons, including the headquarters of the Iraqi secret police, he believes he returned to the Military Police Headquarters before he was finally released. "We were taken from here and handed over to the Red Cross. A guard came into the cell one morning and said: 'The war is over, you will be going home in twenty minutes'. "I literally got down on my knees and said a prayer of thanks. I couldn't believe that I had survived. "People at home have told me I am mad to come back. But things are very different when there is a war on. "There is no doubt, that I encountered some very evil people when I was a prisoner who did some terrible things to me. "But I never believed that all Iraqis were like that and coming back has just reaffirmed that."

The Brigadier smiles and replies in Arabic: "This is part of our nature to treat everybody in an excellent way." Despite the terror of his time in Iraq, John confesses to feeling a certain fondness for his time in this prison. On one occasion, he was summoned by the guards to play football with them. "They came into my cell and asked me if I could play." says John smiling. "When I said yes, we came out here into the courtyard and they put me in goal. "They kept shouting "Gascoigne", and "Kevin Keegan" at me, and I'd nod and say "yes, they are good footballers. It was bizarre." Minutes later, after John's story has been explained to the Brigadier, he has summoned his guards - and a football - and an impromptu game begins. It is a bizarre, but emotional scene. John, casually dressed in jeans and a shirt, kicks the ball to the Iraqi guards, who despite the blistering heat and their heavy uniforms, throw themselves vigorously into the game. Within moments, the courtyard is echoing with the sounds of shouts and laughter as John and the men tackle each other playfully. Dozens of other officers pack into the courtyard, cheering them on and clapping and cheering. When the game ends, the Iraqi players hug and kiss him on both cheeks, asking to have their photograph taken with the curious British airman who was once their prisoner. "You have an excellent football team" he says to the Brigadier. "I think it's Iraq 2, England 0." The Brigadier signals that it is time to leave and insists we join him for tea inside a gazebo built from palm trees and specially reserved for guests. John takes one last lingering look at the cell before turning and following the Brigadier, attempting to make conversation with the help of a translator. "Sometimes when you don't play for a long time and then you come back, you are very unfit." The Brigadier tells him, smiling and fingering a set of turquoise worry beads. John laughs and nods in agreement. The Brigadier adds: "It's all the drinking you have been doing." "You have been spying on us" jokes John through the translator. When we are invited to stay for lunch, he adds: "If we say no, will you allow us to leave?" "Of course", smiles the Brigadier, "You are free to go." The last time, John heard these words spoken was on March 5, 1991. After being moved to two other prisons, including the headquarters of the Iraqi secret police, he believes he returned to the Military Police Headquarters before he was finally released. "We were taken from here and handed over to the Red Cross. A guard came into the cell one morning and said: 'The war is over, you will be going home in twenty minutes'. "I literally got down on my knees and said a prayer of thanks. I couldn't believe that I had survived. "People at home have told me I am mad to come back. But things are very different when there is a war on. "There is no doubt, that I encountered some very evil people when I was a prisoner who did some terrible things to me. "But I never believed that all Iraqis were like that and coming back has just reaffirmed that."

The contrast between John's first and second 'visits' to Iraq could not be more stark. Since becoming one of the most enduring faces of the Gulf War, he has co-written an account of his ordeal and having left the RAF, now works full time as a thriller writer. "If you had said to me then that in ten years time, you will be back here having tea with an Iraqi brigadier I would never have believed you." he adds. As a prisoner, John saw virtually nothing of the country which has become so isolated from the rest of the world since the economic sanctions imposed at the end of the Gulf War. This time around, he is keen to meet as many people as possible and extend the arm of friendship. At sunset, as we walk along the banks of the River Tigris which cuts through the heart of Baghdad, John meets a former Iraqi prisoner of war, who was released from Iran seven month ago. Former soldier Hadi Abdulamir spent 20 years in captivity after his capture during the Iran/Iraq war. As the sound of the Moslem call to prayer echoes across the water, they sit and share their experiences. Hadi tells John how he was whipped and beaten after being caught writing poetry dedicated to his leader Saddam Hussein. John tells Hadi of his own ordeal and the men shake hands and clasp each other. "It just makes you realise that war affects everybody in the same way, whether they are in the military or civilians" says John pensively. "Deep down, we are all the same - human beings. Coming back to Iraq has reassured me of that."

DAILY MIRROR- EXCLUSIVE from Barbara Davies in Baghdad

THE TORNADO was skimming the Iraqi desert at just 50 feet when the missile struck. Thrown sideways by the blast, it erupted into flames, streaking through the air like a fireball. Inside, Flight Lieutenant John Nichol screamed at his pilot: "We've been hit! We've been hit!" The airmen battled to control the stricken aircraft taking it into a steep climb before preparing to eject into enemy territory. But John's last transmission from the crippled war plane was never received. Today, the skies above the southern Iraqi desert where John crashed are virtually empty. The silence is occasionally disturbed by the whine of British and US jets patrolling the no-fly zone imposed on Iraq at the end of the Gulf War nearly ten years ago. On the deserted main runway of Ar Rumaylah military air base, John is standing on the runway he was trying to destroy seconds before his mission came to a violent end. Beside him, shrapnel and rubble surrounds a 40-foot crater carved out of the airstrip by an Allied bomber sent to complete the task. "This is what we were trying to do when we were shot down." Explains John. "This was the start of the end of my war." says John. "The start of the worst seven weeks of my life. At the time of the Gulf War, the air base guarded Iraq's biggest oil field, close to the border with Kuwait. Now there is nothing left. Hangers and accommodation blocks have long since been bombed and bulldozed - Ar Rumaylah is just a ghostly shadow in the middle of the desert.

We have driven hundreds of miles from Baghdad to reach southern Iraq in a bid to trace John's last moments before capture. The effects of 20 years of warfare and economic sanctions are all too clear. Cars on the road are old and patched together, their windscreens cracked - spare parts are virtually impossible to find although petrol is cheaper than water. On the side of the road, veiled women sell camel and goat cheese for a pittance and shopkeepers, whose shops have been destroyed by bomb damage, lay out their wares on table cloths. Reaching Al Basrah, the main city in this area, John flinches as an air raid siren begins wailing, a stark reminder that Allied jets are still bombing on a daily basis. Our hotel, once frequented by wealthy businessman visiting this oil rich region, is jaded and shabby. The swimming pool is empty, the bathrooms still bear the signs of bomb damage, new fixtures and fittings are unobtainable. Armed with letters of access from the Iraqi Ministry of Defence, we arrive at one of the few occupied air bases left in the south, Shaibah, to ask permission to retrace John's steps. An Iraqi MIG warplane on display above a portrait of Saddam Hussein dominates the main entrance where guards stare incredulously at the documentation we show them. "I can't believe they're going to let us in." says John shaking his head. "They must be laughing their heads off." It suddenly seems unbelievable to us that a group of Britons would be allowed onto an Iraqi military base, but our prayers are answered by the arrival of the base commander, Staff Colonel Ala Salman Dawood.

THE TORNADO was skimming the Iraqi desert at just 50 feet when the missile struck. Thrown sideways by the blast, it erupted into flames, streaking through the air like a fireball. Inside, Flight Lieutenant John Nichol screamed at his pilot: "We've been hit! We've been hit!" The airmen battled to control the stricken aircraft taking it into a steep climb before preparing to eject into enemy territory. But John's last transmission from the crippled war plane was never received. Today, the skies above the southern Iraqi desert where John crashed are virtually empty. The silence is occasionally disturbed by the whine of British and US jets patrolling the no-fly zone imposed on Iraq at the end of the Gulf War nearly ten years ago. On the deserted main runway of Ar Rumaylah military air base, John is standing on the runway he was trying to destroy seconds before his mission came to a violent end. Beside him, shrapnel and rubble surrounds a 40-foot crater carved out of the airstrip by an Allied bomber sent to complete the task. "This is what we were trying to do when we were shot down." Explains John. "This was the start of the end of my war." says John. "The start of the worst seven weeks of my life. At the time of the Gulf War, the air base guarded Iraq's biggest oil field, close to the border with Kuwait. Now there is nothing left. Hangers and accommodation blocks have long since been bombed and bulldozed - Ar Rumaylah is just a ghostly shadow in the middle of the desert.

We have driven hundreds of miles from Baghdad to reach southern Iraq in a bid to trace John's last moments before capture. The effects of 20 years of warfare and economic sanctions are all too clear. Cars on the road are old and patched together, their windscreens cracked - spare parts are virtually impossible to find although petrol is cheaper than water. On the side of the road, veiled women sell camel and goat cheese for a pittance and shopkeepers, whose shops have been destroyed by bomb damage, lay out their wares on table cloths. Reaching Al Basrah, the main city in this area, John flinches as an air raid siren begins wailing, a stark reminder that Allied jets are still bombing on a daily basis. Our hotel, once frequented by wealthy businessman visiting this oil rich region, is jaded and shabby. The swimming pool is empty, the bathrooms still bear the signs of bomb damage, new fixtures and fittings are unobtainable. Armed with letters of access from the Iraqi Ministry of Defence, we arrive at one of the few occupied air bases left in the south, Shaibah, to ask permission to retrace John's steps. An Iraqi MIG warplane on display above a portrait of Saddam Hussein dominates the main entrance where guards stare incredulously at the documentation we show them. "I can't believe they're going to let us in." says John shaking his head. "They must be laughing their heads off." It suddenly seems unbelievable to us that a group of Britons would be allowed onto an Iraqi military base, but our prayers are answered by the arrival of the base commander, Staff Colonel Ala Salman Dawood.

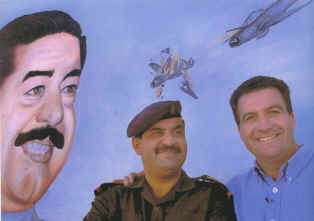

His initial suspicion quickly disappears when he and John begin reminiscing about the war. "You are John Nichol?" he asks staring intently at John. John nods. "You fly the Tornado?", John nods again. "How many hours." continues the Colonel, referring to the time John has completed in the air. "2,000", says John and the Colonel replies. "I also have 2,000." The two airmen, who ten years ago, might have fought in combat, being laughing and smiling, joking with each other as they launch into their experiences. Colonel Ala was shot down just ten days after John, ejecting from his MIG when it was attacked by US Eagles. "It happens in war." says Colonel Ala, whose forehead still bears the scars of his ejection. "We are airmen. We are the same. "I haven't flown a plane for six years. Now, only the birds are free to fly. It is terrible for a pilot." John takes out the photographs of his wrecked Tornado taken by British intelligence officers. In his pocket, he tells the Colonel, he has the co-ordinates he took just seconds before ejecting. "This is my plane in your desert." he says. "I was captured and taken to another air base somewhere around here. Will you help us." The Colonel agrees, but not before we have had lunch with him. We return to the air base to collect a military escort. The Colonel orders one of his men to fetch his pistol, and guards dressed in olive green uniforms and sky-blue berets throw their Kalashnikov rifles into the back of our car and climb in.

His initial suspicion quickly disappears when he and John begin reminiscing about the war. "You are John Nichol?" he asks staring intently at John. John nods. "You fly the Tornado?", John nods again. "How many hours." continues the Colonel, referring to the time John has completed in the air. "2,000", says John and the Colonel replies. "I also have 2,000." The two airmen, who ten years ago, might have fought in combat, being laughing and smiling, joking with each other as they launch into their experiences. Colonel Ala was shot down just ten days after John, ejecting from his MIG when it was attacked by US Eagles. "It happens in war." says Colonel Ala, whose forehead still bears the scars of his ejection. "We are airmen. We are the same. "I haven't flown a plane for six years. Now, only the birds are free to fly. It is terrible for a pilot." John takes out the photographs of his wrecked Tornado taken by British intelligence officers. In his pocket, he tells the Colonel, he has the co-ordinates he took just seconds before ejecting. "This is my plane in your desert." he says. "I was captured and taken to another air base somewhere around here. Will you help us." The Colonel agrees, but not before we have had lunch with him. We return to the air base to collect a military escort. The Colonel orders one of his men to fetch his pistol, and guards dressed in olive green uniforms and sky-blue berets throw their Kalashnikov rifles into the back of our car and climb in.

Driving through the desert, dozens of camouflaged tanks lie partially hidden in the sand, in the distance, the flames of the Ar Rumaylah oil fields light up the horizon like torches. "If you'd told me ten years ago that I'd be here with an Iraqi pilot, I'd have thought you were mad." says John laughing."This is incredible. "I never thought we would be able to come back and see this. "Ten years ago, I tried to bomb his country and now, we are here together as equals. My heart feels very full." The Colonel smiles: "There must be something very special inside you to return to Iraq." At another bombed-out air base, Jalibah, the twisted wreckage of several Iraqi MIGs lie surrounded by the rubble of their hangars. While Colonel Ali and his men look at the scene in dismay and turn away, John studies the rusting remnants of the planes, shards of wing lie next to battered engines. With the help of our translator, he turns to one of the soldiers and says: "How do you feel towards me, knowing that I came to your country to do this to you?"

The young guard, Waleed Khalid, has a look of defiance in his eye when he replies: "It's not a matter of bearing malice towards you, but I would ask what you think of your country coming all this way to bomb us. How do you feel about that?" John nods, and says: "Politics aside, I was carrying out orders as you carry out your orders." They shake hands, and in Arabic, Waleed tells John he is welcome in his country. When John first set foot on Iraqi soil, he was harnessed to an orange and white parachute and visible for miles around, it was only a matter of time before Iraqi soldiers captured him and pilot John Peters. Somewhere, nestling in the vast expanse of sand, the wreckage of John's Tornado has been lying for the last ten years. Equipped with a map and a compass, we drive for an hour through the featureless desert, towards the co-ordinates John has kept for the last decade. He knows that the chances of finding his plane are slim - the exact location it crashed to the ground could have been at least a mile from his last known position. At one stage our vehicle becomes engulfed in the sand. With the help of the soldiers, we dig it out with our hands and continue on, until the Colonel orders us to stop. The stretch of desert lying in front of us, he says, has been landmined and to drive through it would be madness. But if John's Tornado is beyond our reach, we have arrived at the point where John believes he was captured. "It was somewhere out there." he says, pointing into the distance. The vehicles the soldiers came in would have come along this same track. "John Peters and I were laughing because we couldn't have been more visible if we'd tried. "There was nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. It was a terrible feeling, we were so exposed. "For a moment, we thought about taking them on and going out in a blaze of glory, but it was John who made me realise that there is always hope." For an hour, the two airmen made their way across the desert, praying they would be rescued by Combat Search and Rescue. They soon realised they had been spotted when they made out a red truck half a mile away and when Iraqi soldiers opened fire, they decided to surrender. When they stood up, hands raised, they immediately hit the ground again, as another round of fire from the Iraqi's AK-47 rifles scattered around them. Eventually the gunfire stopped and the men were told to get up by an Iraqi officer accompanied by several Bedouin tribesmen. At gunpoint, they were stripped of their pistols, radio, watches and the £1,000 in gold sovereigns they carried with them. Their hands were tied behind their backs and they were pushed into the back of the truck before being driven to a nearby air base - the first of many locations they were taken to during their seven weeks as prisoners of war. John stands for a moment, gazing towards the horizon before taking a few cautious steps towards the no-go area. At his feet, the empty cases of bullet cartridges lie rusting in the sand. John picks up a couple in his hand: "These could even be from the guns they fired at us." he says.

The young guard, Waleed Khalid, has a look of defiance in his eye when he replies: "It's not a matter of bearing malice towards you, but I would ask what you think of your country coming all this way to bomb us. How do you feel about that?" John nods, and says: "Politics aside, I was carrying out orders as you carry out your orders." They shake hands, and in Arabic, Waleed tells John he is welcome in his country. When John first set foot on Iraqi soil, he was harnessed to an orange and white parachute and visible for miles around, it was only a matter of time before Iraqi soldiers captured him and pilot John Peters. Somewhere, nestling in the vast expanse of sand, the wreckage of John's Tornado has been lying for the last ten years. Equipped with a map and a compass, we drive for an hour through the featureless desert, towards the co-ordinates John has kept for the last decade. He knows that the chances of finding his plane are slim - the exact location it crashed to the ground could have been at least a mile from his last known position. At one stage our vehicle becomes engulfed in the sand. With the help of the soldiers, we dig it out with our hands and continue on, until the Colonel orders us to stop. The stretch of desert lying in front of us, he says, has been landmined and to drive through it would be madness. But if John's Tornado is beyond our reach, we have arrived at the point where John believes he was captured. "It was somewhere out there." he says, pointing into the distance. The vehicles the soldiers came in would have come along this same track. "John Peters and I were laughing because we couldn't have been more visible if we'd tried. "There was nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. It was a terrible feeling, we were so exposed. "For a moment, we thought about taking them on and going out in a blaze of glory, but it was John who made me realise that there is always hope." For an hour, the two airmen made their way across the desert, praying they would be rescued by Combat Search and Rescue. They soon realised they had been spotted when they made out a red truck half a mile away and when Iraqi soldiers opened fire, they decided to surrender. When they stood up, hands raised, they immediately hit the ground again, as another round of fire from the Iraqi's AK-47 rifles scattered around them. Eventually the gunfire stopped and the men were told to get up by an Iraqi officer accompanied by several Bedouin tribesmen. At gunpoint, they were stripped of their pistols, radio, watches and the £1,000 in gold sovereigns they carried with them. Their hands were tied behind their backs and they were pushed into the back of the truck before being driven to a nearby air base - the first of many locations they were taken to during their seven weeks as prisoners of war. John stands for a moment, gazing towards the horizon before taking a few cautious steps towards the no-go area. At his feet, the empty cases of bullet cartridges lie rusting in the sand. John picks up a couple in his hand: "These could even be from the guns they fired at us." he says.

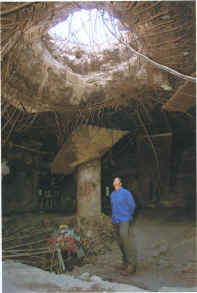

Back in Baghdad, John and I decide to visit the Amiriya Shelter, which has been turned into a shrine to the 400 Iraqi men, women and children who were killed there when it was hit by a bomb. It is not a comfortable decision for John, and walking through the doors of the shelter, he is uneasy and unusually quiet. The Iraqis call it the most savage crime of the century. On February 14, 1991, two US missiles hit the concrete building. The US claims it was a military target and that the civilians placed above it were being used as a human shield. Whatever the truth, photographs of piles of bodies hanging on the inside of the shelter reveal the shocking effects of the bomb and John is all too aware that once, at the controls of his plane, he could have caused such destruction. Inside, a giant hole has been torn through the centre of the shelter which, after the bodies were removed, has been left as it was on the day it was bombed. Row after row of bouquets and flowers have been placed beside portraits of the victims. "I don't know what it is, but you can feel that something hideous happened here." he says. "I don't think people have any concept of the devastation caused by modern warfare. It's easy for us to forget how civilians are affected by war. "Just because you are sitting at the controls of a plane doesn't mean you are blissfully unaware of what is going on beneath you." says John. "War is not a computer game. "In the military, you follow orders. We don't start wars. Politicians do. "It's not that I don't have any feelings. I have seen people killed and when I was a prisoner of war in Iraq, our prison was bombed. It was a terrifying experience. I know what the reality is. "Coming back here has made me see the wider view. I feel very privileged to have been able to do that." On the last day of our trip to Baghdad, John begins packing his bags for the 12 hour drive across Iraq to Amman in Jordan from where we will fly home to Britain. He is, he says, strangely depressed and emotionally drained after the events of the past few days. "Before I came back, I thought it would be exciting. Now I feel quite strange, melancholic." he says. "People here have gone out of their way to help me. I feel I've made friends with them, but I don't know if I will ever come back. "I will carry on with my life and they will carry on with theirs. I wonder if our paths will ever cross again." "In the desert, I picked up one of the empty bullet cartridges as a souvenir. And when we got back to Baghdad, I threw it away. "I suddenly thought. I don't want that to be my souvenir, my memory of this trip. "Before I came back to Iraq, my strongest memories of this country were obviously those of being a prisoner here. "I look back at the time with a mixture of feelings. With a degree of horror, but in a strange way, with fondness. "I can't get away from the fact that it was a major part of my life. Everything changed from that point. "Now, I have the abiding memory of meeting the Iraqis as a free man for the first time. I have walked side by side with people who were once my enemies. That is what I will take home with me."

Back in Baghdad, John and I decide to visit the Amiriya Shelter, which has been turned into a shrine to the 400 Iraqi men, women and children who were killed there when it was hit by a bomb. It is not a comfortable decision for John, and walking through the doors of the shelter, he is uneasy and unusually quiet. The Iraqis call it the most savage crime of the century. On February 14, 1991, two US missiles hit the concrete building. The US claims it was a military target and that the civilians placed above it were being used as a human shield. Whatever the truth, photographs of piles of bodies hanging on the inside of the shelter reveal the shocking effects of the bomb and John is all too aware that once, at the controls of his plane, he could have caused such destruction. Inside, a giant hole has been torn through the centre of the shelter which, after the bodies were removed, has been left as it was on the day it was bombed. Row after row of bouquets and flowers have been placed beside portraits of the victims. "I don't know what it is, but you can feel that something hideous happened here." he says. "I don't think people have any concept of the devastation caused by modern warfare. It's easy for us to forget how civilians are affected by war. "Just because you are sitting at the controls of a plane doesn't mean you are blissfully unaware of what is going on beneath you." says John. "War is not a computer game. "In the military, you follow orders. We don't start wars. Politicians do. "It's not that I don't have any feelings. I have seen people killed and when I was a prisoner of war in Iraq, our prison was bombed. It was a terrifying experience. I know what the reality is. "Coming back here has made me see the wider view. I feel very privileged to have been able to do that." On the last day of our trip to Baghdad, John begins packing his bags for the 12 hour drive across Iraq to Amman in Jordan from where we will fly home to Britain. He is, he says, strangely depressed and emotionally drained after the events of the past few days. "Before I came back, I thought it would be exciting. Now I feel quite strange, melancholic." he says. "People here have gone out of their way to help me. I feel I've made friends with them, but I don't know if I will ever come back. "I will carry on with my life and they will carry on with theirs. I wonder if our paths will ever cross again." "In the desert, I picked up one of the empty bullet cartridges as a souvenir. And when we got back to Baghdad, I threw it away. "I suddenly thought. I don't want that to be my souvenir, my memory of this trip. "Before I came back to Iraq, my strongest memories of this country were obviously those of being a prisoner here. "I look back at the time with a mixture of feelings. With a degree of horror, but in a strange way, with fondness. "I can't get away from the fact that it was a major part of my life. Everything changed from that point. "Now, I have the abiding memory of meeting the Iraqis as a free man for the first time. I have walked side by side with people who were once my enemies. That is what I will take home with me."

This article and pictures are copyright Daily Mirror and may not be reproduced without permission